Money Mistakes Retirees Make

You’ve worked hard and found yourself in a position where you’re finally able to retire. Life is supposed to be easier at that point, right? Instead, retirees face a whole host of new issues that they have to address. Whether it’s government-mandated distributions from their retirement accounts, navigating the best way to fulfill your charitable goals, or simply rebalancing your portfolio to meet you where you are, there are a number of hurdles that present themselves as you age.

Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs)

A required minimum distribution (RMD) is the amount you must withdraw from your retirement account each year. You generally have to start taking withdrawals from your IRA, SEP IRA, SIMPLE IRA, or retirement plan account when you reach a certain age.

If you turned 70 ½ in 2019, you were required to take your first RMD by April 1, 2020. From 2020 to 2022, the law required you to take your first RMD by April 1 of the year after you reach 72. On December 29, 2022, the 2023 omnibus appropriations bill was signed into law, which contained Secure Act 2.0 retirement provisions. The law increased the IRA RMD age, so the age for RMD from an IRA is increased to 73 effective on January 1, 2023. In 2033, the age for RMD increases to 75. After the initial RMD, subsequent RMDs must be taken by December 31 of every year thereafter.

How is the RMD calculated? The IRS has a worksheet you can use to determine your RMD based on the value of your retirement account at the end of the previous year and your life expectancy. So, your RMD for 2023 would be based on the value of your retirement account at the end of 2022.

What happens if you don’t take your RMD? Through 2022, the penalty for not taking a RMD was 50% of the amount required to be withdrawn. Beginning in 2023, the penalty was reduced to 25% of the amount required to be withdrawn, and to 10% if corrected within two years.

So what if you don’t have a need for the money? First, if you expect your retirement plan to have a positive return for the year, it makes the most sense to delay taking the RMD until later in the year. This allows that money to grow tax-free for a longer period of time. Of course, once you take your RMD, you have to pay taxes on the distribution.

There is a way to fulfill the RMD requirement and avoid paying taxes on the distribution (assuming you don’t need the money), and that’s through the use of a qualified charitable donation (QCD). A QCD is a direct transfer of funds from your IRA, payable directly to a qualified charity. Amounts distributed as a QCD can be counted toward satisfying your RMD for the year, up to $100,000 (the annual QCD maximum will be indexed for inflation beginning in 2024). While the QCD doesn’t count as an itemized deduction, the QCD is excluded from your taxable income.

Charitable Giving

We saw in the previous section how making a qualified charitable contribution as all or part of your RMD could save you money because it is excluded from your taxable income. That is one way to meet the desire to support charitable causes while minimizing taxes. There are other ways to do it as well, but often people overlook or are unaware of the best way to take advantage of tax laws when it comes to charitable giving.

An often overlooked strategy when making a donation of several thousand dollars or more is to take advantage of the opportunity to donate appreciated stock instead of cash. When dealing with a charitable contribution of stock, you can deduct the full fair market value (FMV) of the stock at the time it is donated. This can help you to meet your charitable goals, be able to deduct the FMV of the stock from your income taxes, and avoid paying taxes on the gain at the same time.

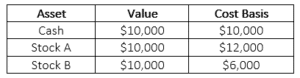

Let’s look at an example to see how this all plays out. Let’s assume that you want to make a $10,000 donation to a public charity. Let’s also assume that you are in the 20% marginal tax bracket (for purposes of this illustration, we assume it is 20% on all forms of income, including capital gains). If you have the following three assets, what would be the most tax-efficient way to give $10,000 to the charity?

If you give the $10,000 in cash to the charity, you can deduct the full amount, and your tax savings would be $2,000. That’s not the worst way to do it, but there are better ways.

If you give Stock A to charity, you can deduct the FMV of $10,000, producing the same amount of tax savings ($2,000) as gifting cash. In this case, however, you would be missing out on another tax-saving opportunity. If you sold Stock A first, you would realize a capital loss of $2,000 (saving you $400 in taxes using our assumptions), then you could donate the cash, resulting in a total tax savings of $2,400.

Then we come to Stock B, which has the potential to provide the most or the least tax savings, depending upon how it is handled. If you sell Stock B and donate the $10,000 to charity, you have a tax savings of $2,000 on the donation, but you realized a $4,000 capital gain, which reduces your tax savings by $800.

What happens if you donate Stock B to a charity? By donating the stock, you avoid paying tax on the $4,000 gain, and you get to deduct the full $10,000 market value of the stock. Yes, you only realize $2,000 in tax savings when filing your taxes, but you avoid the $800 you would pay in taxes from selling it. In effect, you achieve $2,800 in total tax savings, making it the most tax-efficient way to give $10,000 to the charity.

When thinking about charitable giving, it’s important to consider the most efficient way to meet your goals. That not only allows you to fulfill your current charitable goals, but allows you to continue making a difference for years to come.

Portfolio Allocation

You may have heard about the “set it and forget it” type of investing. In fact, when you first started out investing, that may have been what you did. The idea is that you build your portfolio and then you step away from actively managing it. You allow your investments to grow over time, and when you’re young, that’s proven to be a winning strategy.

If we look at the rolling 30 year returns for the S&P 500 since 1926, the worst 30 year period resulted in average annual returns of 7.8%. That means that if you were 25 and invested $1 in something that tracked the S&P 500’s return, at worst it would be worth $9.52 at the end of 30 years. That’s not a bad return, which is why young people are encouraged to begin investing in the stock market early.

However, as you get older and your time horizon for investing changes, you might need to consider changing how you’re invested. If you look at the rolling 20 year returns of the S&P 500, the worst 20 year period returned just 2% annually—still positive, but not the robust returns you would get at 30 years. When you reduce the time period to 10 years, you can have big returns (21.4% was the best period) but also losses (down nearly 5%). Needless to say, the shorter the time period, the more your returns can fluctuate.

Every situation is different, depending upon your income from other sources and risk tolerance. But some general rules of thumb have been developed. You may have heard of age-based asset allocation guidelines like the Rule of 100. The Rule of 100 determines the percentage of stocks you should hold by subtracting your age from 100. If you are 60, for example, the Rule of 100 advises holding 40% of your portfolio in stocks.

As life expectancy has increased, the Rule of 100 has been modified to the Rule of 110, and even the Rule of 120. It works the same way, with you subtracting your age from 110 or 120 to determine what your equity allocation should be. But remember that these are just rules of thumb. If you’re in good health, have a family history of longevity and no need for the money you have invested, you can be more aggressive in your approach. If you’re in poor health and are risk averse, you may want to be more conservative in your equity allocation.

What you don’t want to do is approach things in retirement the same way you approached them when you first started out. As you age and your needs change, so should your portfolio. It should reflect who you are now, not who you were 30 years ago.

As you get older, it can be hard to keep track of everything you’re supposed to stay on top of. By working with a professional financial adviser, they can help keep track of your financial situation and give you clear, objective advice to ensure that your financial goals are met. Find someone that you’re comfortable with and let them help guide you on your financial journey and avoid some of the common pitfalls out there.

About Chase Investment Counsel

Chase Investment Counsel is a family and employee-owned boutique wealth management firm that offers personalized investment services. Our clients include career professionals, those nearing or in retirement, and families experiencing financial transitions such as generational wealth transfer, widowhood, divorce, or sale of a business. Chase’s active, disciplined investment management team is focused on selecting individual stocks and bonds targeted to each investor’s specific financial goals and risk tolerance. Established in 1957 in Charlottesville, VA, Chase Investment Counsel manages more than $300 million in assets.