You are now leaving the Chase Investment Counsel website and entering the Chase Growth Fund website.

Healthcare in Retirement

There is probably no subject more important – and more complicated – to successful retirement planning than the issue of health care costs in retirement. There is nothing further from the truth in that thought that once we turn 65 Medicare will take over our health care expenses. In most cases, Medicare will be the foundation of health care coverage, but there will be a need for thousands of dollars of spending over the 20-30 or more years that one can spend in retirement. There are two overriding subjects to be contemplated: what will my coverage look like and how will it be paid for?

Note the paragraph below from Boston-based investment behemoth Fidelity Investments, which does an excellent annual review of health care spending.

Fidelity Investments®, one of the industry’s most diversified financial services firms and a leader in creating dynamic employee benefits programs, today announced its 20th annual Retiree Health Care Cost Estimate. According to Fidelity, a 65-year-old, opposite-gender couple retiring this year can expect to spend $300,0003 in health care and medical expenses throughout retirement. For single retirees, the 2021 estimate is $157,000 for women and $143,000 for men.

The $300,000 sum for a couple seems overwhelming and in many cases it will be. But remember, this sum is spread over the lives of two people and over a span of two or three decades. This note is not meant to be a comprehensive guide to health care in retirement; it is meant to briefly cover three main areas people should be concerned about and which may allow for some financial planning in prior years. The three areas are health insurance, health savings accounts and long-term care insurance.

As noted above, for the great majority of us, Medicare will become our primary source of health insurance once we reach age 65. There are some exceptions. If you are covered by an employer’s post-retirement health care plan, if you are a government retiree, and if you continue to work (and your employer has more than 20 employees) are three of the most common.

The basics of Medicare are fairly simple: Part A covers hospital and similar care, Part B covers doctor visits, outpatient care, physical therapy, lab tests and a variety of other services. Part A is free but has a deductible of about $1,500 per year and daily co-insurance for some hospital stays. Part B has a base cost of about $150 per month and a small deductible ($203) but also some copayments that are 20% of many services and items. It is important to note that Plan B costs rise for individuals with incomes of $88,000 and couples with incomes of $176,000. The cost ranges from $208 to about $505 per month for people in these income bands.

In addition to Part A and B, it is highly advisable to get a Medicare Part D plan that covers prescription drugs. Part D plans are sold by individual companies and their price will vary depending on deductibles, copayments and the brand name and generic drugs that they will cover. High income individuals and couples will pay more for Part D coverage depending on marital status and modified adjusted gross income.

As if understanding Parts A, B and D aren’t enough, there are numerous private health plans called Medicare Advantage policies that individuals can purchase. The Medicare Advantage policies bundle Parts A, B and D with coverage for items and services not covered under A &B. They are sold by many different companies and their premiums vary by location and by services covered. They come with their own set of letters and cover differing amounts of various services, copayments and deductibles not covered by Plans A & B. These various plans go by letters G, K, L, M and N. The nuances of each of these plans are somewhat subtle to the layman and it is probably wise to seek the help of an insurance professional well versed in these subtleties in researching the various plans.

The second major health care financing consideration many of us will face is whether to purchase long-term care insurance. Although most know what long-term care insurance is, for those who don’t it is a policy that will pay so much per day for your care, or your spouse’s care, in an institution or pay a sum to have some of that care performed at home. The care is triggered by whether someone can no longer perform two of six normal activities of daily living (ADL) such as bathing, dressing, eating, getting out of bed, etc. Like other types of insurance, long-term care requires an application. If and when you or a spouse needs to use the policy a claim will be made, reviewed, and approved by the insurance company that sold you the policy. Similar to a “deductible,” long term care policies have “elimination periods” of 30-90 days for which you are responsible for care.

Deciding whether or not to purchase it is as much an emotional decision as a financial decision and is wrapped up as well in the decision on what type of housing to seek in retirement. In some ways, long-term care insurance is most like buying whole life insurance in that you pay annual premiums for many years before the payday comes, for your beneficiaries, at least, when you die. Most long-term care policies are purchased by people in their 50s or 60s, with the “payday” not usually seen for 20-30 years. A key difference is that the “payday” in long-term care insurance might never be reached. About ½ of today’s 65-year-olds are likely to require some long-term care services, so ½ are not. Most individuals use long-term care for less than two years, but some 15% will require more than five years of long-term care services.

The key reasons for considering purchasing long term insurance are similar to the reasons for buying other types of insurance – you pay a smaller sum now to secure a larger sum of money in the future should you need it. In the case of long-term care, coverage can come eventually from Medicaid, but only after an individual spends down the great bulk of his or her assets and only if the individual needing care is willing to go into an institution that accepts Medicaid. In sum, people often buy coverage to protect the assets they have built over the years and also to give themselves more options for higher quality long-term care if needed and not be reliant solely on facilities and services that accept Medicaid.

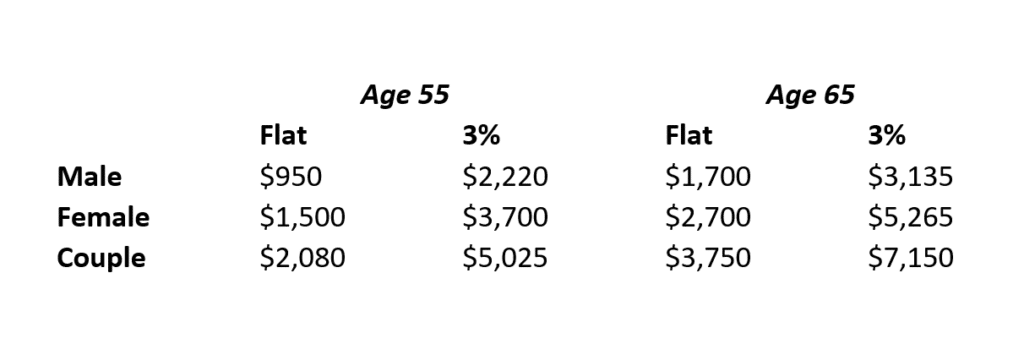

Like life insurance, long-term care insurance is cheaper when bought early. Other factors that influence costs include the health of the applicant(s), gender, marital status, amount and type of coverage sought and the insurance company selling the plan. The numbers become fairly large quickly. The table below shows the annual cost of a long-term care policy with a $165,000 pool of benefits (per person) for males, females, and couples, both on a “flat” basis and with benefits rising 3% per year. Although “flat” benefits make policies much less expensive than inflation-adjusted benefits, one should remember that health care costs have traditionally risen faster than inflation in the past.

One will note that costs are much larger for females than males. This is due to the longer expected life spans for women. One positive of long-term care policies compared to other policies, is that federal tax laws allow for long-term care premiums to count as deductible medical expenses for those who itemize their tax returns and for whom medical expense are large enough.

A key question to ponder is whether the $150,000 ($5,000 x 30) a couple is likely to pay for long-term care insurance over 30 years (and that is if premiums stayed flat), would have been better off invested in something that grows in value more than the benefit which would have grown to about $400,000 at 3% over the period. If that same $5,000 per year were invested at 7% per year for 30 years, it would have risen to about $472,000, taxes not included.

As with other insurance policies, the financial strength quality of the insurance company selling the policy is of paramount importance. A decade or so ago, scores of companies sold long-term care policies. Today there are probably fewer than 20 who do so. Early sellers of long-term care policies badly misjudged how long people would live and how benefit costs would rise. The premiums they collected from policyholders along the way were insufficient to pay benefits so many exited the business.

Over the past few years, several insurance companies have started to bundle long-term care policies with life insurance policies including a death benefit. Theoretically, this makes a lot of sense since many people who have paid for long-term care policies will never use them. As with much involving insurance, the devil is in the details regarding products of this type.

After reading the sections on Medicare and long-term term care, many of you might wonder whether there is anything positive about thinking about and planning for health care and retirement. There is. One of the best savings vehicles ever invented are “Health Savings Accounts,” basically self-directed accounts created for the purpose of paying for future health care expenditures.

Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) were created in 2003 as part of the same legislation that created Medicare Part D. Much like Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs), HSAs allow for individuals who are covered by high-deductible health plans to put money in on a pre-tax basis, allow that money to grow free from annual taxes and, unlike traditional IRAs, allow that money to be withdrawn and spent without paying taxes on a broad variety of health care products and services. Also, like IRAs, HSAs come with annual limits on contributions. In 2021, these are $3,600 per individual, $7,200 per family and for those about age 55, a $1,000 catch-up contribution is allowed.

One of the great benefits of HSAs is the broad variety of expenditures that qualify for HSA withdrawals.

This includes spending on items not completely covered by insurance such as medications or medical products and services including dental, vision and chiropractic care. It also includes spending on deductibles and co-payments not covered by insurance. And it also includes premiums for some parts of Medicare coverage, such as Part D, long-term care coverage, and Medicare premiums. Like IRA money, the HSA money can be invested in many ways – stocks, bonds, mutual funds, etc. Many people use HSAs to cover miscellaneous annual health care expenses, but it is also important and usually far wiser to make annual HSA contributions and not use the funds so they can grow until you are no longer permitted to contribute to an HSA (usually age 65) then use the funds for subsequent health care expenditures. In addition, HSA money can be inherited tax-free by a spouse and used for his or her medical expenses.

As with many other government programs, there are a lot of wrinkles in HSAs that may make consulting an expert in the field important. In addition, there is copious information on HSAs from AARP, and many investment organizations.

If you are not sure you are prepared for your retirement years, download our Retirement Planning Primer for key considerations to a successful retirement.